Finding the right amount of AI

Imagine a spectrum. On the far left are humans typing on the keyboard, seeing the code in the IDE. On the far right: AGI. It implements everything on its own. Cheaply, flawlessly, better than any human, and no human overseer is required. Somewhere between those two extremes is the right amount of AI for your coding process, and it’s available today. That threshold moves to the right every week as models improve, tools mature, and workflows get refined.

Recently I stumbled upon this awesome daxfohl comment on HN:

Which is higher risk, using AI too much, or using AI too little?

and it made me think about LLMs for coding differently, especially after reading what other devs share on AI adoption in different workplaces. You can be wrong in both directions.

The question isn’t “should I use AI?”. The question is: where’s the threshold this week?

How We Got Here

Not long ago the first AI coding tools like Cursor (2023) or Copilot (2022) emerged. They were able to quickly index the codebase using RAG, so they had the local context. They had all the knowledge of the models powering them, so they had an external knowledge. Googling and browsing StackOverflow wasn’t needed anymore. Cursor gave the users a custom IDE with built in AI powered autocomplete and other baked-in AI tools, like chat, to make the experience coherent.

Then came the agent promise. MCPs, autonomous workflows, articles about agents running overnight started to pop up left and right. It was a different use of AI than Cursor. It was no longer an AI-assisted human coding, but a human-assisted AI coding.

Many devs tried it and got burned. Agents made tons of small mistakes. The AI-first process required a complete paradigm shift in how devs think about coding, in order to achieve great results. Also, agents often got stuck in loops, hallucinate dependencies, and produced code that looks almost right but isn’t. You needed to learn about a completely new tech, fueled by FOMO. And this new shiny tool never got it 100% right on the first try.

Software used to be deterministic. You controlled it with if/else branches, explicit state machines, clear logic. The new reality is controlling the development process with prompts, system instructions, and CLAUDE.md files, and hope the model produces the output you expect.

Then Opus 4.5 came out.

The workflows everyone were talking about just worked, out of the box. Engineers transitioned to Forward Deployed Engineers, becoming responsible for many other things than coding. Sometimes not even coding by hand at all. Recently Spotify’s co-CEO Gustav Söderström said

An engineer at Spotify on their morning commute from Slack on their cell phone can tell Claude to fix a bug or add a new feature to the iOS app. And once Claude finishes that work, the engineer then gets a new version of the app, pushed to them on Slack on their phone, so that he can then merge it to production, all before they even arrive at the office.”

I hope they at least review the code before merging.

The next stage is an (almost) full automation. That’s what many execs want and try to achieve. But Geoffrey Hinton predicted in 2016 that deep learning would outperform radiologists at image analysis within five years. Anthropic’s CEO predicted AI would write 90% of code within three to six months of March 2025. None of this happened as predicted. The trajectory is real, but the timeline keeps slipping.

Your Brain on AI

In 2012, neuroscientist Manfred Spitzer published Digital Dementia, arguing that when we outsource mental tasks to digital devices, the brain pathways responsible for those tasks atrophy. Use it or lose it. Not all of this is proven scientifically, but neuroplasticity research shows the brain strengthens pathways that get used and weakens ones that don’t. The core principle of the book is that the cognitive skills that you stop practicing will decline.

Margaret-Anne Storey, a software engineering researcher, recently gave this a more precise name: cognitive debt. Technical debt lives in the code. Cognitive debt lives in developers’ heads. It’s the accumulated loss of understanding that happens when you build fast without comprehending what you built. She grounds it in Peter Naur’s 1985 theory that a program is a theory existing in developers’ minds, capturing what it does, how intentions map to implementation, and how it can evolve. When that theory fragments, the system becomes a black box.

Apply this directly to fully agentic coding. If you stop writing code and only review AI output, your ability to reason about code atrophies. Slowly, invisibly, but inevitably. You can’t deeply review what you can no longer deeply understand.

The insidious part is that you don’t notice the decline because the tool compensates for it. You feel productive. The PRs are shipping. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s research on flow showed that the state of flow depends on a balance between challenge and skill. Your mind needs to be stretched just enough. Real flow produces growth. Rachel Thomas called what AI-assisted work produces “dark flow”, a term borrowed from gambling research, describing the trance-like state slot machines are designed to induce. You feel absorbed, but the challenge-skill balance is gone because the AI handles the challenge. It feels like the flow state of deep work, but the feedback loop is broken. You’re not getting better, you’re getting dependent.

No Code, Only Review

There’s this observation that keeps coming up in HN comments: if the AI writes all the code and you only review it, where does the skill to review come from? You can’t have one without the other. You don’t learn to recognize good code by reading about it in a textbook, or a PR. You learn by writing bad code, getting it torn apart, and building intuition through years of practice.

This creates what I’d call the review paradox: the more AI writes, the less qualified humans become to review what it wrote. Storey’s proposed fix is simple: “require humans to understand each AI-generated change before deployment.” That’s the right answer. It’s also the one that gets skipped first when velocity is the metric.

The Seniority Collapse

This goes deeper than individual skill decay. We used to have juniors, mids, seniors, staff engineers, architects. It was a pipeline where each level built on years of hands-on struggle. A junior spends years writing code that is rejected during the code review not because they were not careful, but didn’t know better. It’s how you build the judgment that separates someone who can write a function from someone who can architect a system. You can’t become a senior overnight.

Unless you use AI, of course. Now, a junior with Claude Code (Opus 4.5+) delivers PRs that look like senior engineer work. And overall that’s a good thing, I think. But does it mean that the senior hat fits everyone now? From day one? But the head underneath hasn’t changed. That junior doesn’t know why that architecture was chosen. From my experience, sometimes CC misses a new DB transaction where it’s needed. Sometimes it creates a lock on a resource, that shouldn’t be locked, due to number of reasons. I can defend my decisions and I enjoy when my code is challenged, when reviewers disagree, and we have a discussion. What will a junior do? Ask Claude.

It’s a two-sided collapse. Seniors who stop writing code and only review AI output lose their own depth. Juniors who skip the struggle never build it. Organizations are spending senior time every day on reviews while simultaneously breaking the mechanisms that create it. The pipeline that produced senior engineers, writing bad code, getting torn apart in review, building intuition through failure, is being bypassed entirely. Nobody’s talking about what happens when that pipeline runs dry.

What C-Levels Got Right and Wrong

Look at what lands on C-level desks every week. Microsoft’s AI chief Mustafa Suleyman says all white-collar work will be automated within 18 months. Anthropic’s CEO Dario Amodei predicts AI will replace software engineers in 6-12 months and quoted his engineers saying they don’t write any code anymore, just let the model write it and edit the output. Sundar Pichai (CEO, Google) reported 25% of Google’s new code was AI-generated in late 2024. Months later, Google Research reported that number had reached 50% of code characters. If you’re a CTO watching that curve, of course you’re going to push your teams.

The problem is that predictions come from people selling AI or trying to prop the stock with AI hype. They have every incentive to accelerate adoption and zero accountability when the timelines slip, which, historically, they always do. And “50% of code characters” at Google, a company that has built its own models, tooling, and infrastructure from scratch, says very little about what your team can achieve with off-the-shelf agents next Monday.

AI adoption is not a switch to flip, rather a skill to calibrate. It’s not as simple as mandating specific tools, setting “AI-first” policies, measuring developers on how much AI they use (/r/ExperiencedDevs is full of these stories). A lot of good practices like usage of design patterns, proper test coverage, manual testing before merging, are often skipped these days because it reduces the pace. AI broke it? AI will fix it. You need a review? AI will do it. Not even Greptile or CodeRabbit. Just delegate the PR to Claude Code reviewer agent. Or Gemini. Or Codex. Pick your poison.

And here’s what actually happens when you force the AI usage. One developer on r/ExperiencedDevs described their company tracking AI usage per engineer: “I just started asking my bots to do random things I don’t even care about. The other day I told Claude to examine random directories to ‘find bugs’ or answer questions I already knew the answer to.” This thread is full of engineers reporting that AI has made code reviews “infinitely harder due to the AI slop produced by tech leads who have been off the tools long enough to be dangerous.” Has AI made their jobs faster? Probably. Has it made them enjoy their jobs significantly less? Absolutely.

This is sad, because being able to work with the AI tools is a perk for developers and since it improves pace, it’s something management wants as well. It’s obvious that the people gaming the metrics (not really using the AI) would be fired on the spot if the management learned how they are gaming the metrics (and it’s fair), but they are gaming the metrics because they don’t want to be fired…

Who should be responsible for setting the threshold of AI usage at the company? What if your top performing engineer just refuses to use AI? What if the newly hired junior uses AI all the time? These are the new questions and management is trying to find an answer to them, but it’s not as simple as measuring the AI usage.

This is Goodhart’s law in action: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” Track AI usage per engineer and you won’t get better engineering, you’ll get compliance theater. Developers game the metrics, resent the tools, and the actual productivity gains that AI could deliver get buried under organizational dysfunction.

The Cost Nobody Talks About

The financial cost is obvious. Agent time for non-trivial features is measured in hours, and those hours aren’t free. But the human cost is potentially worse, and it’s barely discussed.

Writing code can put you in a flow state, mentioned before. That deep, focused, creative problem-solving where hours disappear and you emerge with something you built and understand. And you’re proud of it. Someone wrote under your PR “Good job!” and gave you an approval. Reviewing AI-generated code does not do this. It’s the opposite. It’s a mental drain.

Developers need the dopamine hit of creation. That’s not a perk, it’s what keeps good engineers engaged, learning, retained, and prevents burnout. The joy of coding is probably what allowed them to become experienced devs in the first place. Replace creation with oversight and you get faster burnout, not faster shipping. You’ve turned engineering, the creative work, into the worst form of QA. The AI does all the art, the human folds the laundry.

Finding Your Threshold

I use AI every day. I use AI heavily at work, I use AI in my sideprojects, and I don’t want to go back. I love it! That’s why I’m worried. I’m afraid I became addicted and dependent. I’ve implemented countless custom commands, skills, and agents. I check CC release notes daily. And I know many are in similar situation right now, and we all wonder about what the future brings. Are we going to replace ourselves with AI? Or will we be responsible for cleaning AI slop? What’s the right amount of AI usage for me?

AI is just a tool. An extraordinarily powerful one, but a tool nonetheless. You wouldn’t mandate that every engineer uses a specific IDE, or measure people on how many lines they write per day (…right?). You’d let them pick the tools that make them most effective and measure what actually matters, the work that ships.

The right amount of AI is not zero. And it’s not maximum. It’s a deliberate, calibrated choice that depends on context, and it changes as models improve.

Software engineering was never just about typing code. It’s defining the problem well, understanding the problem, translating the language from business to product to code, clarifying ambiguity, making tradeoffs, understanding what breaks when you change something. Someone has to do that before AGI, and AGI is nowhere close (luckily). You’re on call, the phone rings at 3am, can you triage the issue without an agent? If not, you’ve probably taken AI coding too far. If the AI usage becomes a new performance metric of developer, maybe using AI too often, too much, should be discouraged as well? Not because these tools are bad, but because the coding skills are worth maintaining.

The Risk of Too Little

If you’re using no AI at all in 2026, you are leaving real gains on the table:

- Search and context. AI is genuinely better than Google for navigating unfamiliar codebases, understanding legacy code, and finding relevant patterns. This alone justifies having it in your workflow (since 2023, Cursor etc)

- Boilerplate and scaffolding. Writing the hundredth CRUD endpoint, config file, or test scaffold by hand when an agent can produce it in seconds isn’t craftsmanship, it’s stubbornness. Just use AI. You’re not a CRUD developer anymore anyway, because we all wear many hats these days (post 2025 Sonnet)

- The workflow itself. The investigate, plan, implement, test, validate cycle that works with customized agents is a real improvement in how features get delivered. Hours instead of days for non-trivial work. It’s not the 10x that was promised, but 2x or 4x on an established codebases is low-hanging fruit (post 2025 Opus 4.5)

- Exploration. “What does this module do? How does this API work? What would break if I changed this?” AI is excellent at these questions. It won’t replace reading the code, but it’ll get you to the right file in the right minute. (since 2023)

Refusing to use AI out of principle is as irrational as adopting it out of hype.

The Risk of Too Much

If you go all-in on autonomous AI coding (especially without learning how it all actually works), you risk something worse than slow velocity, you risk invisible degradation:

- Bugs that look like features. AI-generated code passes CI. The types check. The tests are green. And somewhere inside there’s a subtle logic error, a hallucinated edge case, a pattern that’ll collapse under load. In domains like finance or healthcare, a wrong number that doesn’t throw an error is worse than a crash. (less and less relevant, but still relevant)

- A codebase nobody understands. When the agent writes everything and humans only review, six months later nobody on the team can explain why the system is architected the way it is. The AI made choices. Nobody questioned them because the tests passed. Storey describes a student team that hit exactly this wall: they couldn’t make simple changes without breaking things, and the problem wasn’t messy code, it was that no one could explain why certain design decisions had been made. Her conclusion: “velocity without understanding is not sustainable.” (will always be a problem, IMO)

- Cognitive atrophy. Everything in the Digital Dementia section above. Skills you stop practicing will decline. (will always be a problem, IMO)

- The seniority pipeline drying up. Also covered above. This one takes years to manifest, which is exactly why nobody’s planning for it. (It’s a new problem, I have no idea what it looks like in the future)

- Burnout. Reviewing AI output all day without the dopamine of creation is not a sustainable job description. (Old problem, but potentially hits faster?)

The threshold moves to the right every week. But we are nowhere near AGI. The models are getting better. Genuinely, measurably better. But “better” is not “good enough to replace human judgment,” and every prediction about when we’d get there has been wrong. LLMs are language models. They predict tokens.

The Quiet Decline

Here’s what keeps me up at night. By every metric on every dashboard, AI-assisted human development and human-assisted AI development is improving. More PRs shipped. More features delivered. Faster cycle times. The charts go up and to the right.

But metrics don’t capture what’s happening underneath. The mental fatigue of reviewing code you didn’t write all day. The boredom of babysitting an agent instead of solving problems. The slow, invisible erosion of the hard skills that made you good at this job in the first place. You stop holding the architecture in your head because the agent handles it. You stop thinking through edge cases because the tests pass. You stop wanting to dig deep because it’s easier to prompt and approve. There’s no spark in you anymore.

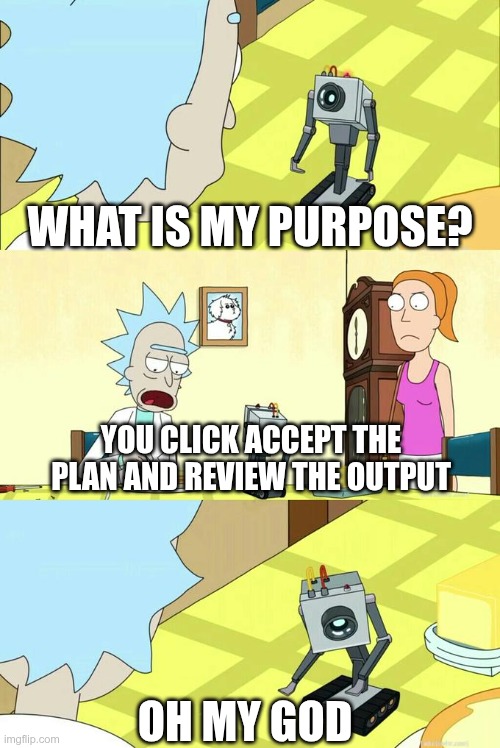

In this meme the developers are the butter robot. The ones with no mental capacity to review the plans and PRs from AI, will only click Accept, instead of doing the creative, challenging work. Oh the irony.

Simon Willison, one of the most ambitious developer of our time, admitted this is already happening to him. On projects where he prompted entire features without reviewing implementations, he “no longer has a firm mental model of what they can do and how they work.”

And then, one day, the metrics start slipping… Not because the tool got worse, but because you did. Not from lack of effort, but from lack of practice. It’s a feedback loop that looks like progress right up until it doesn’t.

No executive wants to measure this. “What is the effect of AI usage on our engineers’ cognitive abilities over 18 months?” is not an easy KPI. It doesn’t fit in a quarterly review. It doesn’t get tracked, and what doesn’t get tracked doesn’t get managed, until it shows up as a production incident that nobody on the team can debug without an agent, and the agent can’t debug either.

I’m not anti-AI, I like it a lot. I’m addicted to prompting, I get high from it. I’m just worried that this new dependency degrades us over time, quietly, and nobody’s watching for it.